Thomas Cahill's How the Irish Saved Civilization is one of those really frustrating books whose overall value fluctuates depending on what chapter you're currently in. It's rather like that old Longfellow rhyme:

There was a little girl,

Who had a little curl,

Right in the middle of her forehead.

When she was good,

She was very good indeed.

But when she was bad she was horrid.

The Good

Cahill was an American from the Bronx, but a reader could be forgiven for thinking he was an Irishman--an Irishman with a deep love for his native land. Via abundant quotes and translation of historic Irish poetry and tales, he brings us in to a land of song and grass, war and weeping, where the women are beautiful and dangerous, and the men are "generous, handsome, brave." His chapter on pre-Christian Ireland paints a wonderful picture of the barbarian north--the sort of thing that C.S. Lewis fell in love with. But his portraits of this world, and the world of dying Roman order far to the south, are merely the introduction to a wonderful story--one that is often overlooked.

The Very Good

"The word Irish is seldom coupled with the word civilization. When we think of peoples as civilized or civilizing, the Egyptians and the Greeks, the Italians and the French, the Chinese and the Jews may all come to mind. The Irish are wild, feckless, and charming, or morose, repressed, and corrupt, but not especially civilized."

When we think civilization, we think books. All the classics that we love--Plato, Cicero, Homer--were part of the ancient world that was Rome. But when the barbarians poured over northern Europe, Italy, and Africa, the books and the educated class largely disappeared. The Christians were gone from Britain. The Christians were gone from northern Gaul. The Christians had not made it into Germany. The people of the Book were gone, and so books were gone as well. And in the midst of this intellectual darkness, one man stepped off the boat and took on an entire island. His name was Patrick.

Cahill tells his story with dash and verve. As the first man (besides the legend of St. Thomas in India) to bring the Gospel to a non-Roman world, Patrick had a unique task. He fulfilled that task with unprecedented success. Ireland became Christian--a rough, melodramatic, song-filled sort of Christianity that took Ireland's long warrior ethic and channeled it into wars of another sort. They destroyed the slave trade, and were the first in Europe to do so. They built tiny monasteries where wise men taught their brethren how to subdue the flesh and practice unstinting hospitality.

"Ireland is unique in religious history for being the only land into which Christianity was introduced without bloodshed. There are no Irish martyrs (at least not till Elizabeth I began to create them eleven centuries after Patrick). And this lack of martyrdom troubled the Irish, to whom a glorious death by violence presented such an exciting finale. If all all Ireland had received Christianity without a fight, the Irish would just have to think up some new form of martyrdom...the Irish of the late fifth and early sixth centuries soon found a solution, which they called the Green Martyrdom, opposing it to the Red Martyrdom by blood. The green martyrs were those who, leaving behind the comforts and pleasures of ordinary human society, retreated to the woods, or a mountaintop, or to a lonely island...there to study the Scriptures and commune with God." (151)

And when they were alone in their tiny, beehive-shaped oratories, they learned languages--having even then the Irish gift of gab--and copied books. And their unstinting love of all words is the reason that many of the classics survived. Unlike on the continent, where churchmen like Jerome worried that he loved Cicero more than God and many monks simply copied over classic vellums, the Irish collected, copied, added, collated. As more and more monks fled the chaos of the continent, their collections grew. They trained anyone to read and write in them--noble or lowborn, man and woman. Cahill says it well:

"Like the Jews before them, the Irish enshrined literacy as their central religious act. In a land where literacy had previously been unknown, in a world where the old literary civilizations were fast sinking beneath successive waves of barbarism, the white Gospel page, shining in all the little oratories of Ireland, acted as a pledge: the lonely darkness had been turned into light, and the lonely virtue of courage, sustained through all the centuries, had been transformed into hope." (163-4)

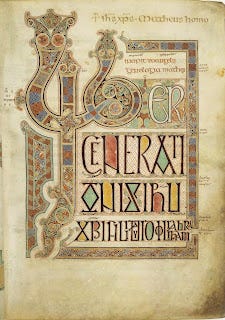

Lindisfarne Gospels, Matt. 1:1

Irish monks invented miniscule that would become the common script of the medieval period. Irish monks trained men to produce beautifully illustrated jewels of books that wound up in libraries all across Europe. And when the Green Martyrdom grew commonplace and easy, monks like the famous Columcille (better known by his Latin name, Columba) of Iona took up the "White Martyrdom" of sailing off into the white morning and leaving Ireland for foreign shores. He taught unlettered Scotland the faith--and letters. His successors (as Bede somewhat grouchily records) did the same for Angleland. Others went to the Gauls, still more to the Lombards of northern Italy, founding monasteries as they went. They took their books with them.

"The Hebrew bible would have been saved without them, transmitted to our time by scattered communities of Jews. The Greek Bible, the Greek commentaries, and much of the literature of ancient Greece were well enough preserved at Byzantium and might still be available to us somewhere--if we had the interest to seek them out. But Latin literature would almost surely have been lost without the Irish, and illiterate Europe would hardly have developed its great national literatures without the example of the Irish, the first vernacular literature to be written down." (193)

Alcuin and Boniface, both, were trained by Irish monks. From them we trace the cathedral schools that grew into the universities, which led eventually to the Reformation, universal education, and the world we know today. It is a truly thrilling story, told by an able author who paints it very well.

The Horrid

And yet... when Cahill whiffs, he whiffs so badly that it makes me doubt the good parts. I would highlight two major problems: the assumption that Christianity develops over time (and some of it shouldn't) and his view of classical learning.

In his later chapters especially, he regularly (though subtly) criticizes Ireland from moving away from the egalitarian and sexually free society of the early pagans to the harsh, regimented, patriarchal character of the continental church. By abandoning their ancient customs for such harsh impositions, Ireland was abandoning diversity for stultifying uniformity.

"It would be a reckless overstatement to claim that women possessed equality in Irish society; but their larger presence here ensured a greater stress on physical amenities and on the value of intimacy (Ita, a sixth-century hermit-foundress was thought to have been granted the ecstatic privilege of nursing the Christ-child at her own virgin breasts). This larger female presence also contributed to the teeming variety of Irish religious life--a variety that would have distressed the Romans, had they known of it. They would have been even more disturbed had they known of the wide-ranging activities of the high abbesses, whose hands had the power to heal, who almost certainly heard confessions, probably ordained clergy, and may have celebrated Mass."

The idea that one of his prized books, the Bible itself, might mandate abandoning some of these frontier practices apparently never enters his head. One can easily imagine Cahill sneering at the hopelessly backward and repressed Romanists of his own day; indeed, some of his material seems deliberately picked to mess with them. As he dryly notes, "Such goings on, though of great antiquity, still have the power to shock the more piously orthodox." As for classical learning, consider his opinion of Cicero:

"We are made uncomfortable and bored by Cicero's elaborately coaching us in all the tricks of his trade--the many techniques for convincing others to act the way we ant them to. For Cicero, to 'speak from the heart' would be the rashest foolishness; one must always speak from calculation...how [may I] dazzle my listeners so they are no longer able to reason matters through independently? The techniques of the successful politician, the methods of modern advertising, the whole panoply of persuasion is to be found in Cicero. The figure closest to him in our own age might be Dale Carnegie, who advised that every single word and gesture be calculated to 'win' and 'influence.'" (47)

This is, at best, grossly unfair to Tully. It smacks more of a modern prejudice against those Cahill calls "Cicero's contemporary children: publicists, marketers, all those who seek to motivate us to do what we might otherwise not do." (49) One is reminded of the modern canard that ancient rhetoric was all about power, not love. This is an area I happen to know a bit about, and I would argue that this is not even close to Cicero's project. Far from being a mere purveyor of "cheap success" he genuinely believed in using one's talents and education to benefit fellow men:

“The greatest necessity is that of doing what is honorable, next to that is the necessity of security, and the third and last is the necessity of convenience or ease, this can never stand comparison with the other two." (De Inventione)

“The supreme orator, then is the one whose speech instructs, delights, and moves the minds of his audience. Docere debitum est, delectare honorarium, permovere necessarium. (The orator is duty bound to instruct; giving pleasure is a free gift to the audience, but to move them is indispensible.)” (De Optimo Genere Oratorum)

Cahill is taking cheap shots to make his preference for Virgil's poetry over Cicero's philosophy sound better. That he is doing so in a chapter about Augustine of Hippo, rhetor extraordinaire, is ironic at best.

The End

But his opinion of the ancients does not diminish the great gratitude he obviously feels to the Irish for preserving them. And as classical education enters its own renaissance, we too ought to join him in thanking God for a little green isle on the edge of the world, and the men and books in it who saved civilization for us.